Superman's Mullet

A Lesson in Game Design

Most comic book superheroes have a history: famous battles with their friends or enemies, plotlines everyone remembers, old flames that come and go. That time they lost their powers. That time they died, before the time they came back. We call this history “continuity” and it’s very weird because superhero stories expect readers to both know and ignore continuity at the same time.

Clark Kent has been Superman for going on 90 years, and over that time he’s built up a lot of continuity. A lot of history. He’s been Superboy. He’s gone to the 30th century. He’s been a newspaper reporter, a TV news anchor, and a novelist. He’s gotten married. He’s died. Sometimes a new story references one of those things he did in the past, and you get more out of that story if you remember or recognize the reference.

But, at the same time, every once in a while DC tries to reset continuity and say, oh no, all those old stories somehow don’t count, don’t remember those. Remember these new stories instead. And sometimes that works and sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes the corporate process gets in the way, creators aren’t all on the same page, and they start referencing continuity which has been, officially, thrown out. And sometimes a creator like Grant Morrison comes along and ignores all the edicts to throw out continuity, instead choosing to embrace everything, every story, even when they’re contradictory and can’t possibly all be true.

That’s what I mean when I say that comics expects you to both know, and selectively ignore, continuity. It’s a big demand. Continuity is a barrier to new readers. And this is not just a comics problem; every Marvel Universe project now is resting on top of 10+ years of story; if you didn’t see Eternals, so you don’t know there’s the corpse of a titianic space god standing in the Indian Ocean, well, Harrison Ford will have to explain it to you in the next movie. But don’t think about it too hard, because if you do you may start to wonder “Oh hey, what about those Eternals? What happened to them?” That’s the part we want you to forget. Nothing to see here.

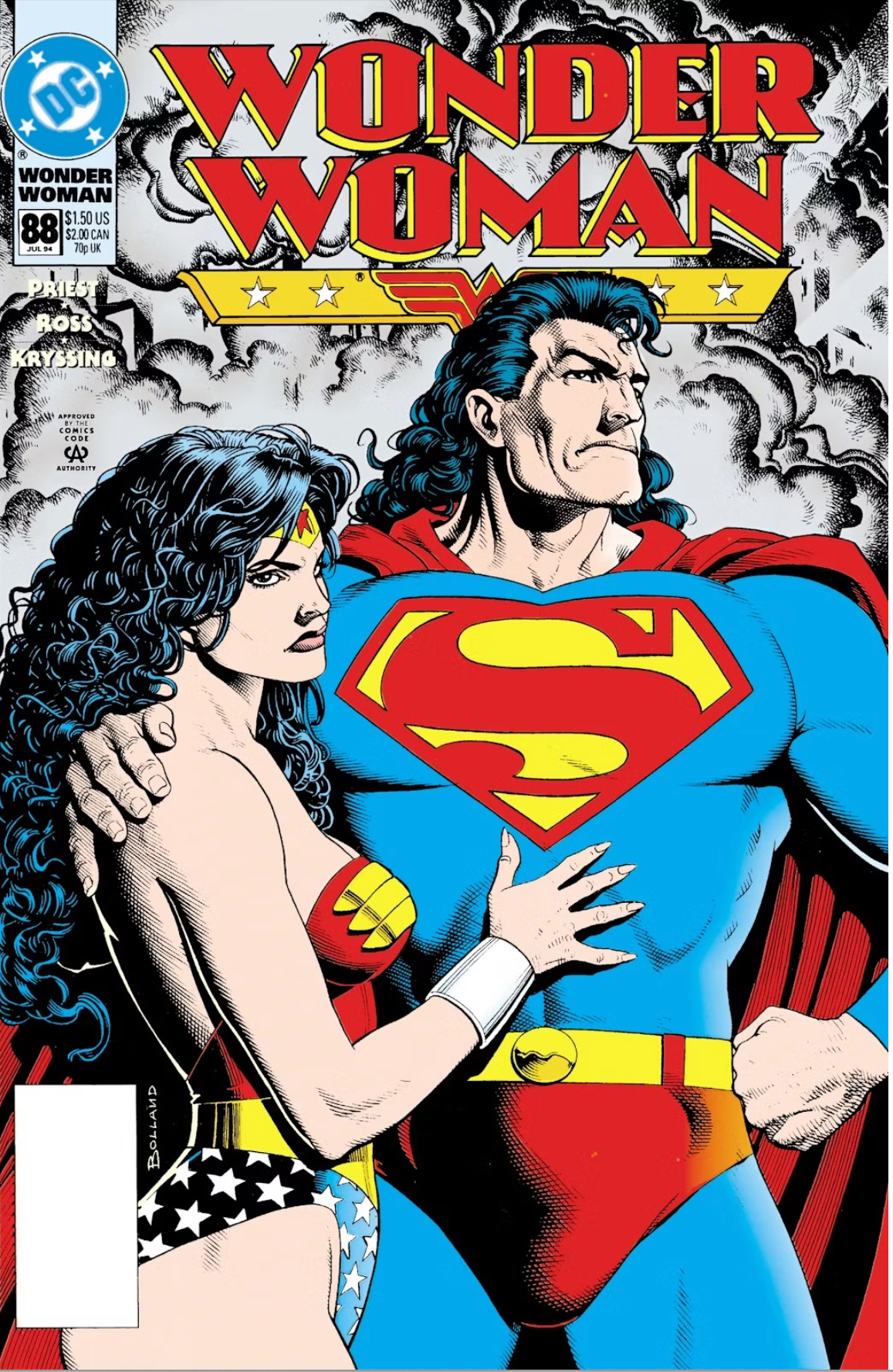

Continuity can teach us an important lesson in game design. Let’s use a specific example, illustrated by that frankly AMAZING Brian Bolland cover at the top of this essay. Back in the 90s, Superman had a mullet. He’d just come back from the dead, and it was the 90s. No further explanation is necessary, really. Nowadays we old time comics dudes tend to make fun of this sort of thing. But Superman is not alone in his moment of embarrassing continuity. Every character that’s been around for more than a few issues has something like this. That time Captain America wore a suit of armor for a year. That time the Avengers helped Ms. Marvel marry her rapist. The entire Clone Saga.

But see, here’s the thing, for a lot of readers coming to Superman in the 1990s, that was their Superman. Maybe they were kids buying Superman off the spinner rack or in a 7-11 (something that still occasionally happened even in the 90s). Maybe they’d avoided Superman for a long time, been drawn in by the “Death of Superman” story, and now that he’d been resurrected they were like, okay, now it’s time for business in the front and party in the back. Whatever. I don’t know.

But what I do know is that for someone out there, probably more than one someone, that version of Superman is their favorite version of the character. They would die for the Super Mullet.

Now, let’s say you’re a new writer or artist or editor on Superman. And to you, this whole mullet period is grossly embarrassing. What are you going to do? Are you going to say it never happened? You could do that. You are in creative control. You could erase that time, change continuity (we call this a “retcon”), and say, well, if Superman is in his 30s now, in 2024, that means he was a kid in the 90s, and he hadn’t become Superman yet, so there was no Super-Mullet. You could say that.

But, honestly, why should you? Because when you do that, you’re alienating that fan who, when he thinks of Superman, the first image that comes to him is that Brian Bolland cover (go look at it again, it’s still AMAZING). Now you’re telling that person you’re wrong, there was no mullet. But you’re not a cruel, heartless monster, so you choose not to do that. Instead, you just don’t talk about it. Sure, Superman had a mullet. But if no one ever mentions it, if it has no bearing on any story, then it doesn’t really matter if he had it or not. You can emphasize the elements of continuity you do like, write stories that hook into history you love, and just … not talk about the other stuff. You don’t need to harsh that fan’s mellow.

All of which brings me to the Forgotten Realms.

I’m the project lead for the new Forgotten Realms books recently announced on the Wizards YouTube channel. You can see the video here, I’m only in it for about 30 seconds, the upshot is: two new Forgotten Realms books updating and refreshing the setting.

In the course of this project I had to make some really big creative decisions very early on. And one of those decisions was: what are we gonna do about continuity? Because the Realms has a lot of continuity from multiple sources. There’s decades of TSR and Wizards material, of course, but Ed Greenwood has been working on the setting since he was a kid and he’s still going today. Fans and third party creators have added countless pages to the Realms.

Some of this continuity is pretty clunky. When Wizards created the third, fourth, and fifth editions of D&D, they felt obliged to explain how the rule changes manifested in the fantasy world. This obligation was created by continuity. To take one example, the Symbul was a wizard in 1st and 2nd edition D&D. But when 3rd edition introduced sorcerers, she became a sorcerer and, retroactively, she’s always been a sorcerer. Well, until she died (or did she?).

Wizards designers introduced setting elements like the Spellplague, the Sundering, and the Second Sundering to make the Forgotten Realms fit each successive edition. And this may come as a shock, but blowing your world up can make fans of that world really grouchy.

But the simple fact is that 95% of D&D fans have never played a version of D&D other than 5th edition. They know nothing about the Realms outside of what they’ve (maybe) read in the Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide and in adventures like Rime of the Frostmaiden or Tomb of Annihlation. Most “Realmslore” is completely lost on them and, importantly, we should not require them to learn it! I know the OGs out there have fond memories of Elminster, but if an average player of D&D knows Elminster at all, it’s as a) Mystra’s messenger in Baldur’s Gate 3 or b) Simon’s great grandfather in Honor Among Thieves. Astarion is far, far more recognized by our fans today than Elminster.

So now here I am, looking at fifty years of Forgotten Realms continuity, and I have to ask, “What do I keep? What do I lose? Who do I piss off?” And the answer is: the Spellplague is the mullet of the Forgotten Realms. Sure, yes, there are elements of the Realms that I find kind of dumb, weird, or even offensive. And some of these things, the offensive things, I’m gonna change. But if we don’t need to change it? I’m just not gonna talk about it. Was there a Spellplague? A Sundering? A Second Sundering? Sure. I guess. They might even get a few words each in a sidebar. But really I’m just not talking about them. They’re still out there. And if you are running a 40 year long Realms campaign where the Spellplague was absolutely key, a critical part of continuity, you can keep doing that. We’re not saying the Spellplague didn’t happen. But the vast majority of our players don’t know about the Spellplague, don’t care about it, and are not gonna notice when I don’t talk about it. They’re gonna be way too busy running brand new adventures in an exciting world filled with fresh new faces and new, world-shaking, challenges to overcome.

So once again, I guess we’re all business in the front, and party in the back, my friends. Party in the back.